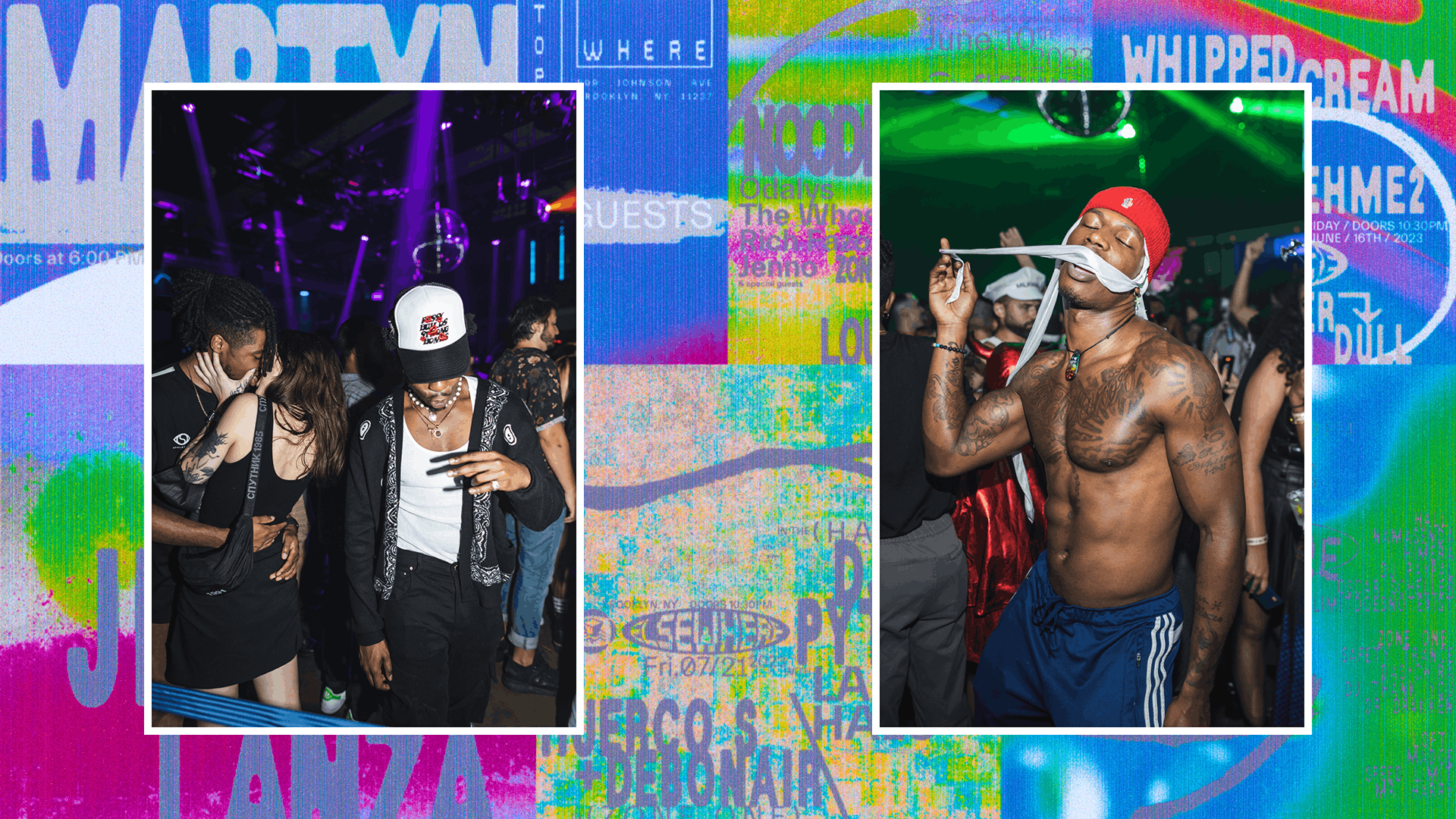

Clubs are where we see people at their best and their worst – and there are often photographers in the midst with the challenging job of documenting an experience that is anything but static.

It’s a task London-based photographer Roxy Lee is happy to take on. “There are always people at a club to show off, and actually it’s just quite fab and I’m here for it,” she says, speaking from her home in Islington. A fixture of London’s queer scene, Roxy is renowned for her 35mm shots – often taken ‘blind’ in the dark – of roving queer club night Adonis. And since 2018, her photos have been synonymous with another queer club night, Inferno – in particular, the inventiveness of the outfits. (One image immortalises a partygoer with lingerie and a fascinator created from sponges, and air fresheners for earrings.) And as each party’s popularity soared, her photographic work took off with it.